Opening of the Southwest

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

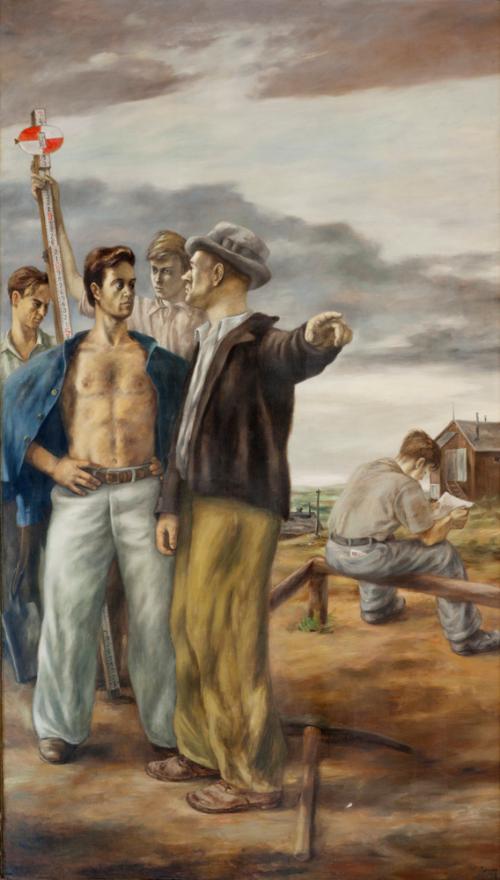

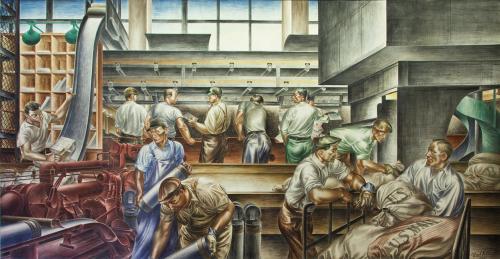

In the nineteenth century, the rugged land of the American West held great practical and symbolic value for settlers. It offered geological grandeur, agrarian opportunity and represented, to many, the destiny of the American people. Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States was ordained to expand westward, had spiritual and religious undertones and was used to justify brutality and Indian removal. It also allowed people, even in the twentieth century, to view the conquest of the West as an inevitable progression. With scenes moving chronologically from left to right, Ward Lockwood's ambitious frescos portray one interpretation of the settlement of the American West against the backdrop of advancements in postal communication.

Opening of the Southwest begins its historical progression with the depiction of one of the earliest inhabitants of the American Southwest. At the far left, a Hopi man performs the traditional Snake Dance while another Native American, wearing only a loincloth and headdress, reclines on the ground. Most likely intended to represent indigenous culture and ancient traditions, these figures are problematic, for reasons described in the text below, titled "American Indians in the American Imagination."

To the right of the Hopi man, a Spanish Conquistador rides on horseback alongside a Franciscan priest. Beginning in the sixteenth century, Spanish Conquistadors and Franciscan clergy traveled northward from Mexico and westward from Florida in search of riches and intent on converting indigenous peoples to Christianity. The Spaniards introduced horses to North America, some of which were set free, escaped, or were stolen. These horses allowed the Plains Indians, pictured in the background, to hunt buffalo.

In the center foreground, a beaver trapper represents the next wave of Western settlers, seventeenth-century frontiersmen who hunted beavers and other animals for fur, which was prized in Europe. Following the trapper, a pioneer family walks determinedly, armed against weather and enemies, on their westward journey. Finally, a prospector with his burro, pick, and pan descends to mine for gold while, in the distance, covered wagons bring settlers and mail to the American West.

American Indians in the American Imagination

A member of the Taos Society of Artists in New Mexico, Ward Lockwood, who lived and worked in the American southwest, possessed a deep appreciation for Native American history and culture. Lockwood completed extensive research while working on his post office murals. He removed an image of an American Indian attacking a white settler, due to his concern that accounts of the event may have been biased or inaccurate. Nonetheless, his murals still objectify Native Americans and reproduce stereotypes that persisted in 1930s American culture. Although he eschews images of American Indian violence, the murals propagate the idea of a submissive and marginalized Native American population.

By the early twentieth century, most American Indian tribes had been removed from their native lands and confined to government reservations. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 encouraged tribal sovereignty, land management, and economic self-sufficiency; however, it did not allow for true tribal self-governance. At this pivotal moment, with the American frontier closing and the Native population in decline, but surviving as sovereign nations, many Americans looked to the past with nostalgia, idealizing their Native forbearers as an exotic but vanishing race.

Public art, including many New Deal commissions, often reinforced this idea. Lockwood's depiction of a Hopi Snake Dancer is one such instance. The Hopi people were one of the earliest groups residing in the American southwest. Their nine-day Snake Dance is performed every other summer as part of a cycle of rituals to bring good weather, fertility, and health. In the late nineteenth century, the final day of the dance was opened to spectators and attracted artists, journalists, and photographers, who saw it as a colorful spectacle of an ancient American cultural past. In 1913, shortly after former President Theodore Roosevelt attended, the Hopi chose to prohibit photography of the Snake Dance due to what they felt was the objectification of the dancers and the transformation of a sacred ritual into a sideshow. While artists continued to praise and reinterpret the dance, Lockwood's depiction diminishes the ritual significance of the Snake Dance, instead using the dancer as a decontextualized signifier of the ancient American West.

The other Native American figures in Lockwood's murals likewise obscure cultural detail in favor of wistful symbolism. The reclining man at the Hopi dancer's feet bears no indication of tribal affiliation, and his posture implies a vanquished people. The inexplicably nude plains Indians hunting buffalo serve as archetypes for all Indian tribes, living wild and freely off the land prior to their impending defeat. And the surrendering chiefs, while regal and appropriately dressed, display a false ease with their captors and enact an idealized, peaceful surrender. Overall, the depictions of Native Americans in Lockwood's murals do not represent malice on the part of the artist, but rather reflect the cultural misconceptions that remained in circulation in the 1930s.