Dangers of the Mail

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

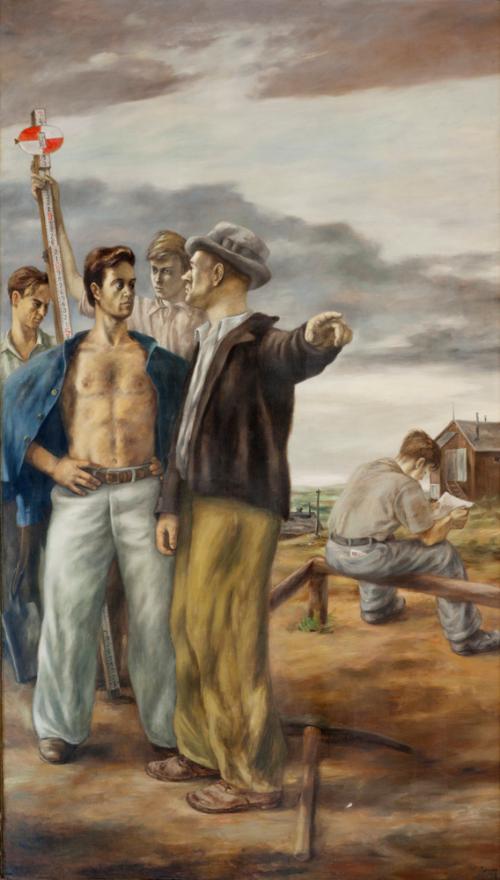

In a document Mechau provided to the Section of Fine Arts in November, 1937, the artist described historic incidents in which Indians attacked armed stage coaches in search of horses, guns, ammunition, and war booty, and to collect scalps. In Dangers of the Mail, Mechau depicted just such a scene. The artist, recruited and championed by Section Assistant Director Edward Rowan for his stylistic daring, wrote that he intended "to create an imaginative reconstruction of a massacre into a pattern of forms." The mural was admired by art critics, who praised its "stirring formal patterns" and "compelling mood," and described it as "spectacular and exhilarating." However, the violent subject matter—Native Americans attacking a stagecoach party, including several nude women, at least two of whom are about to be scalped or strangled—has disturbed many in the decades since its unveiling. (See thematic essay below: "Controversy Then and Now")

Below Dangers of the Mail, Mechau produced five smaller scenes related to the Indian Wars and the Pony Express. Below these, he included the names of 21 Native American leaders, including spokesmen for peace and education—such as Spotted Tail and Plenty Coups—as well as warriors who led the resistance against white settlement of the West—such as Sitting Bull and Ink Paduta. The list also features the famous Oglala Lakota leader Crazy Horse and his comrades Little Big Man and Red Cloud. Along the sides of both murals Mechau painted Indian designs that he discovered during his research at the Salt Lake City library. Mechau's inclusion of Native American names and designs indicates a desire to pay respect to the indigenous tribes. However, these elements have been overshadowed by the aggressive, stereotypical representation of American Indians in the large mural.

Controversy Then and Now

Mechau's murals have provoked controversy since before they were unveiled in September of 1937. In March of that year, the designs were published in Time magazine and drew some pointed criticism. Harry Galbraith, a Colorado news reporter, alleged historical inaccuracies in the paintings. He wrote to Postmaster General James A. Farley that the male figures, horses, and architecture appeared modern rather than historical; that the long rifles held by the settlers in Pony Express should have been Colt revolvers and sheath knives; and finally, that the scalping depicted in Dangers of the Mail would only have been performed after the victim was unconscious, a gruesome but relevant point.

Others were outraged by the indecency of the female nudes in Dangers of the Mail. This issue grew in intensity until Mechau and Section Assistant Director Edward Rowan appeared on Capitol Hill to defend the work. Rowan argued that the nudes were relatively small, were "abstract" and "utterly impersonal," and should be considered "symbolic motifs." In these years, abstraction was related to the modernist movement in art, itself believed by many Americans to be a breach of propriety.

Nonetheless, Mechau was allowed to proceed with his designs, with the condition that he stress historical accuracy. The murals received great praise in some quarters. The press described them as dramatic, poetic, imaginative, and stirring. The president of the Museum of Modern Art, purchased one of the studies for the museum, and it was shown in May 1938 at the Musée du Jeu de Paume in Paris. Section director Edward Bruce stated, "Frank Mechau's paintings alone would have justified the entire PWAP program!" However, condemnation continued. Perhaps most significantly, Commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs John Collier criticized Dangers of the Mail in October 1937. He poked fun at Mechau's claim that the women were not being scalped, only "roughly handled," and he called the mural "a slaughter against pioneer women."

Sixty years after their debut, Mechau's murals again stirred heated debate when employees of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—which now occupies the building—objected to the violence of Dangers of the Mail and the stereotypical depictions of both American Indians and women. In the context of a federal workplace, the murals were cited as creating a hostile work environment. GSA, which oversees the building and its art, consulted with experts, EPA employees, and members of the public, and found opinions to be split: many called for the removal of Dangers of the Mail from the building, while just as many opposed removing or covering the art. A comprehensive interpretive program was created in consultation with both Native Americans and Frank Mechau's children.

Mechau's murals and the controversies surrounding them serve as important reminders. First, they vividly render the tragedy of the Indian Wars of the 1860s; second, they recall the degrading stereotypes and social hierarchies that were widely accepted in the 1930s; and finally, they emphasize the difficulties of addressing these issues, and the role of art in public buildings, even today. The murals are evidence that bold art and problematic subject matter often go hand in hand.