Society Freed Through Justice

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

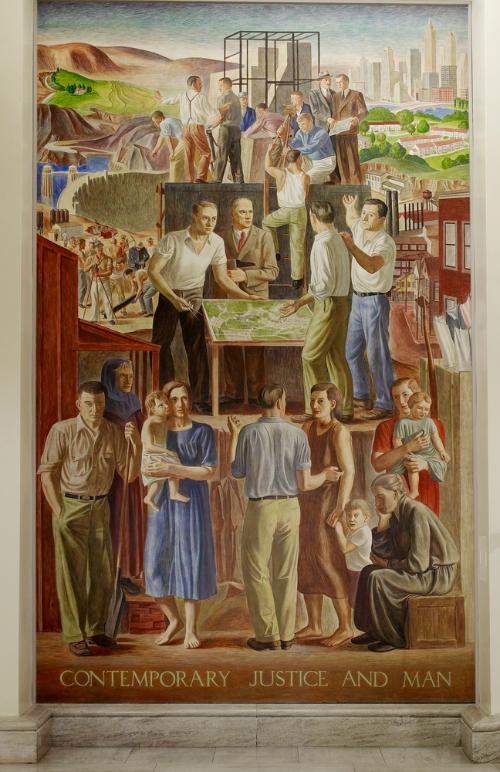

Located in the U.S. Department of Justice Building, Society Freed Through Justice consists of five fresco panels on three walls surrounding a staircase. Pilasters, which are rectangular columns attached to a wall, divide the panels. The first panel on the left wall depicts two floors of a sweatshop factory in an industrial town. Men and women sew garments together in this cramped workroom. The scene also includes children, suggesting the widespread practice of child labor in the 1930s. At the bottom of the panel, an inscription from Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., reads: “The life of the law has not been logic, it has been experience.” By locating the quote on a workbench where two young girls sit, Biddle implies that laws must consider and account for the lived experiences of everyday Americans, including the poor and disadvantaged. In the upstairs room of the factory, the artist includes portraits of prominent men and women as some of the workers. The man behind the sewing machine, who stares out at the viewer, is a self-portrait of the artist. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins appears next to him in a black dress. Behind them stand violinist and author Marian Tyler and her husband—economist, author, and Harvard classmate of Biddle, Stuart Chase.

The panel on the right wall similarly depicts a cross-section of a building, showing the modest homes of working-class Americans. Upstairs, women of several generations tend to household tasks, such as ironing, sewing, and caring for children. Outside, Biddle includes a portrait of fellow artist Henry Varnum Poor as the man sawing wood in the lower right corner. On the first floor of the tenement, men gather around a table playing checkers. In this scene, Biddle represented the faces of “foreign” individuals, including a Jewish man likely from Eastern Europe, other unidentified immigrants, and a Black man, the only Black person in the mural. He is also the only figure shown sleeping, which draws on racist imagery of the idle Black man. While Biddle wished to represent these communities in his mural, he relied on stereotypical depictions. Rather than integrating them into the rest of the composition, he isolated the figures, which marks them as different and separate. At the base of the painting is a quote from Justice Louis D. Brandeis, the first Jew to be named to the Supreme Court: “If we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold.”

The central panels of the mural are Biddle’s imagined scene of “Society Living Under Ideal Social Conditions.” The people portrayed are White, rural, and non-immigrant families. The inscription at the bottom, “The sweatshop and tenement of yesterday can be the life ordered with justice of tomorrow,” draws a contrast between the “idyllic” rural scene at the center and the urban working-class scenes on the flanking walls, which represent “Society Uncontrolled by Justice.” The central scene is anchored by a bountiful supper at a farmhouse table. Once again, Biddle includes portraits of real individuals. Presiding over the meal is Francis Biddle, the artist’s brother and chairman of the National Labor Relations Board, who became Attorney General in 1941. Also at the table is Malcolm Ross, press agent of the National Labor Relations Board, and Biddle’s wife, the sculptor Hélène Sardeau, who holds their son, Michael, in her lap. The man hanging his coat on the back wall is Edward Rowan, the administrator of the Section of Painting and Sculpture. Camille Miller of the National Youth Administration stirs a pot in the kitchen. Helen Hunt—the wife of Henry Hunt, General Counsel of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration—assists Olin Dows, chief of the Treasury Relief Art Project, in planting shrubs in the yard. The man with the shovel is David Elwyn, son of Professor Herman Elwyn of Columbia University, and a neighbor of the Biddles in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. In the background, men carry lunch boxes as they walk to work, toward a river scene likely based on towns along the Ohio River near Wheeling, West Virginia.

In June of 1933, Biddle learned that Congress had allocated funds to decorate the new Post Office and Department of Justice buildings. Artists, like all workers, struggled during the Great Depression. Biddle proposed to his friend and former classmate, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, that the government hire painters to produce murals for these public spaces, suggesting that artists would work for “plumbers’ wages.” Artist and businessman Edward Bruce, who believed in the power of public art to enrich the lives of all Americans, helped persuade the President to approve Biddle’s plan. The goals of the resulting Federal Art Project were four-fold: to create a vital national school of mural art, to encourage the free expression of American artists in conjunction with the social and economic ideas of the administration, to offer financial assistance to artists, and to stimulate American economic recovery.

When the time came to commission artwork for the U.S. Department of Justice building, Biddle suggested artists Maurice Sterne, Leon Kroll, Louis Bouché, Boardman Robinson, John Steuart Curry, and himself. Many of the artists were first or second-generation immigrants from Eastern Europe; no women artists or artists of color were included. Biddle proposed a unified and thematic approach for the artists, which required each to portray the ideals of justice; the styles and subjects varied.

Biddle’s mural proposal had first to be approved by the Commission of Fine Arts, an independent agency founded in 1910 that reviews all projects related to “design and aesthetics” in the nation’s capital. His designs received harsh criticism from CFA and Section officials. Charles Moore, from the CFA, described the sketches as, “disturbingly busy in both pattern and scale,” “too big for the allotted spaces,” “crude and harsh in color … even grotesque,” and lacking in conviction. He also expressed concern that the style was “somewhat French and very Mexican” and “intrinsically un-American and ill-adapted to express American ideas.” Edward Rowan of the Section noted that the faces of the figures on the central wall, living in an “ideal” society, were “not pleasant enough” and that their “pathos and suffering” did not contrast enough with the sweatshop and tenement panels. Edward Bruce, who was head of the Section, and building architect Charles Louis Borie strongly defended Biddle’s work, and Bruce ultimately overturned the CFA’s initial rejection of the sketches. The dispute between the CFA and the Section never reached the public.Biddle chose to paint in true fresco, or “buon fresco.” This technique involves adding pigments directly to wet plaster, which requires the artist to work quickly and deliberately before the plaster dries. For inspiration, Biddle referred to the frescos of the Italian Renaissance, especially the work of Piero della Francesca, and the twentieth-century Mexican muralists, particularly Diego Rivera. Completing Society Freed Through Justice required long working hours, which sometimes began before dawn and lasted for ten to twelve hours.

After the murals’ unveiling, some art critics agreed with the CFA that the color was too bright and the contrast between the unjust and ideal aspects of life were lacking, while others judged Biddle’s murals to be admirable, far exceeding expectations, and the best work of his career.