Sons and Daughters

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

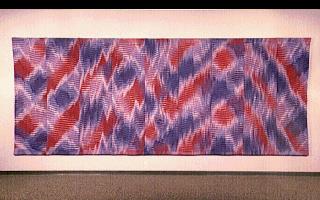

Sons and Daughters, Lia Cook’s innovative hand-woven textile, adds a human element to the United States Courthouse and Post Office. The artist drew on a long tradition found in both photography and painting when designing Sons and Daughters. The artwork is composed of four equally-sized vertical panels attached to one another. Each features an image derived from a snapshot of a child that has been cropped so that the background is largely eliminated and emphasis placed on the face. While all the children are close to the picture plane, each is at a slightly different distance, which creates an illusion of depth and movement both across the four panels and within the depicted space. The girl portrayed in the left panel is most fully visible; the top of her head is cropped, as is her right side. Turned at an almost three-quarter angle, her shoulder, much of her torso, and portions of her hands are included in the picture. The little boy in the next panel seems closer to the viewer; his head, tilted a bit, is also cut off on his right side by the panel’s edge, but it clears the top, and only a portion of his left shoulder can be seen. The sense of forward motion culminates in the third section in which a girl’s face nearly fills the frame. Only a small part of the right side of her head is unseen, and her chin is near the bottom of the panel. The fourth panel introduces a new dynamic motion—in contrast to the other three, the boy enters the frame from the right. The left side of his face falls beyond the picture’s edge and he is positioned further from the foreground, so that like the girl in the first panel, more of his body is included in the picture. Seen as part of an overall composition, his placement creates an upward movement and, with the image in the first panel, frames the center sections of the tapestry.

Comprehension of the images woven into Sons and Daughters changes depending on the viewer’s distance from the tapestry. Up close, only the abstract pointillist patterns of color of the fabric’s weft yarns are visible, creating an effect that recalls the neo-impressionist landscapes of Georges Seurat or the photorealist portraits of Chuck Close. Seen from farther away, the children’s faces emerge from the woven surface, and although the images derive from photographs, the details are muted and slightly granulated as if seen on a fuzzy television screen. Each image depicts an intimate, albeit momentary encounter between child and photographer and, by extension, child and viewer. They are fully aware of being observed and candidly confront the viewer in an inquisitive, yet playful manner. The oversized scale of the images adds to the children’s enveloping presence and to the intimate nature of the experience.

While the gender of the children is apparent, little else is evident. There are two girls and two boys, all are young and appear to have different ethnic backgrounds. We cannot tell if they are rich or poor. Even the bits of clothing that are visible provide little information about when and where the photos may have been shot. Such conscious stripping away of contextual information by Cook leaves us in the presence of the children themselves—sons and daughters—who may represent the growing diversity of the American society, as well as its future.

Additional meaning is brought to the work with its placement in the lobby of a federal courthouse. Every person convicted of a crime was once a child, just like these children. Even though each one of us begins life with a proverbial clean slate, personal circumstances and actions determine whether we end up as a member of the jury, a defendant on trial, or the presiding judge. Cook’s portrayal of these impressionable children serves as an impetus to reflect on our own choices in life.

Cook designed the overall work so that each panel is the same size and no child is visually or compositionally emphasized over another. Rather than one focal point, there are four, which can be interpreted symbolically: regardless of gender, race, or class, each person is viewed equally under law and is treated as such in a federal courtroom. Both the subject and the composition reflect Cook’s hope “that people involved in the court procedures will think about the future of all our children and make the connection that ultimately the legal system will not only determine their particular case or issue, but that those decisions and actions will affect future generations.”