Pony Express

framed: 72 1/2 x 162 in. (184.2 x 411.5 cm)

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

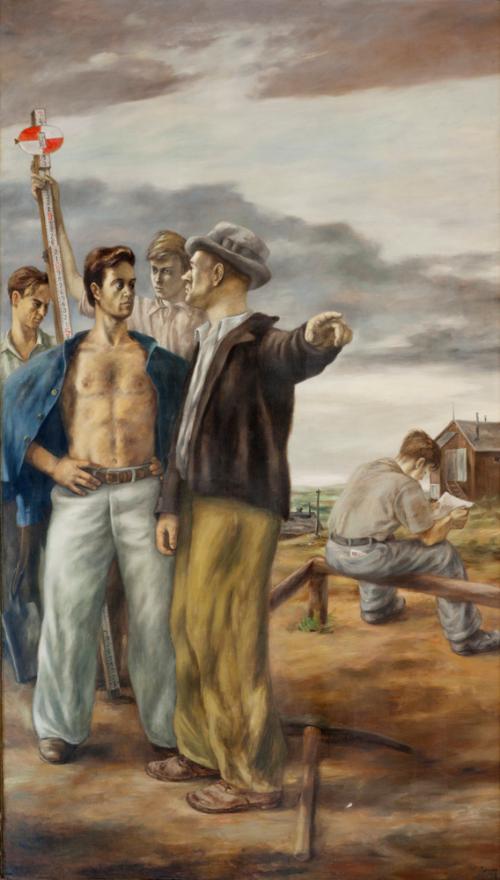

The 1860s were crucial years for American westward expansion and exciting days for the United States Post Office Department. Settlers flooding westward, mining the land and seeking opportunity, necessitated increased mail delivery. Beginning in 1857, private stagecoach companies delivered letters from St. Louis to San Francisco. From April, 1860, until October, 1861, riders of the famed Pony Express raced from the plains to the coast, traveling 75 to 100 miles daily and changing horses at relay stations set ten to fifteen miles apart. The riders' dedication in traversing the rough western landscape underscores the importance of communication in the rapidly growing nation. These same years saw great strife throughout the country. While the Civil War raged in the East, the Indian Wars—dating back at least 40 years—continued to take the lives of settlers and Native Americans in the West. Frank Mechau's murals depict dramatic and violent incidents related to the Pony Express and westward expansion.

The Pony Express, though short-lived, has become a classic symbol of the American West. In the late-19th and early-20th centuries, the daring exploits of famous riders like Buffalo Bill Cody were romanticized in dime novels and Wild West shows. In November, 1937, Frank Mechau presented his personal history of the Pony Express to Section leaders. In this text, Mechau acknowledged white aggression and praised the expertise of the Comanche horsemen who taught white riders, even as he described the threats that Indians posed to Pony Express riders, going so far as to delineate which Indians were friendly to whites and which were hostile.

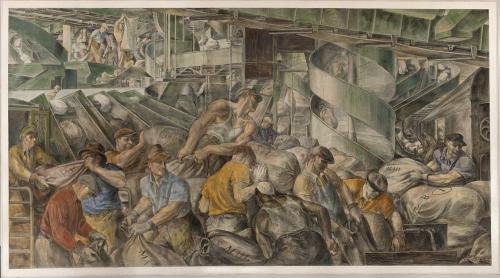

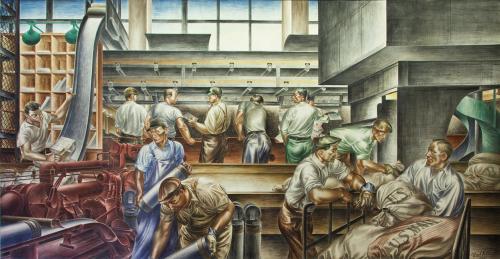

In Pony Express, Mechau likewise paid tribute to the Pony Express while recognizing the turmoil that it produced. The central panel shows the changing of horses at a division point. Above both Pony Express and Dangers of the Mail appear the names of towns along the route of the Pony Express, beginning with San Francisco and ending with St. Joe. Below Pony Express, Mechau listed the names of heroic Pony Express riders, including the celebrated Pony Bob Halsam, who made the longest uninterrupted ride of the Pony Express (round trip 380 miles in 36 hours during the Pyramid Lake War) and Jim Moore, who rode 280 miles in just under 15 hours. Mechau also inscribed the names of Western frontiersmen like Kit Carson—who became a popular dime novel character while also overseeing the mistreatment of thousands of Navajos—and the famous gunslinger Wild Bill Hickok.

For Native Americans, the Pony Express represented the loss of tribal land, food sources, and sovereignty, and its presence in the West led to clashes and armed conflict. Below the main panel of Pony Express, Mechau included a series of pictures illustrating indigenous responses to the threat of the Pony Express, including a scene of Native Americans stealing horses from a station and one of a Native American taking the mochila, or mail bag, from a rider. The ambushing of stations, especially after the Pyramid Lake War of 1860, contributed to the demise of the Pony Express.