This Garden at This Hour

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

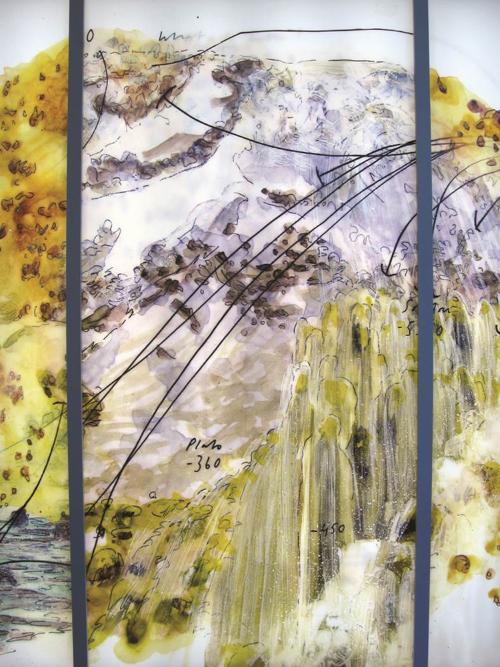

Throughout history and across cultures, gardens have been used to represent the universe in microcosm, invoking archetypal creation stories, and mediating between nature and culture. Following in this tradition, artist Matthew Ritchie created This Garden at This Hour, a sprawling environmental artwork in the form of a garden containing sculptures, paving, furniture and plants, all composed in a complex formal arrangement that Ritchie has described as “an attempt to create a landscape where different kinds of information can coexist; to convey my personal sense of how incredibly rich and complicated the world really is at every level.”

Ritchie is well known for his elaborate, multimedia projects that variously combine drawing, painting, sculpture, sound and video to explore the relationships among many fields of inquiry, such as history, religion, science and literature. With each new project, Ritchie shifts the focus of his artwork’s content to address its specific context. For example, with This Garden at This Hour, Ritchie traces the parallels between archetypal creation stories and the vital work of the FDA. The artwork’s title is an allusion to John Milton’s 17th-century epic poem Paradise Lost (book 9, lines 205–06, “...we labor still to dress this Garden...”), the structure and themes of which Ritchie connects to the idea of growth and change at different levels and scales.

Described by Ritchie as “a molecular garden,” the artwork’s interlocking metal arbors, planters, benches and hexagonal stone pavers are patterned after the structure of carbon, the elemental foundation of life, evoking the complex and important mission of the FDA through both natural and scientific building blocks. Treating the underlying roof surface as an enormous canvas and working with GSA horticulturalist Darren DeStefano, Ritchie carefully selected the artwork’s plantings for their visual and sculptural qualities, historical and medical uses, symbolic meanings (some of which are indicated by their common names), and references to numerous traditions and folklores that feature plants as both foods and medicines. The plantings range widely in scale, from tiny sedums to towering grasses. Almost all are zygomorphic (symmetrical along a single axis), fractally echoing both each other and the forms of the sculptures.

The garden also represents an evolutionary timeline, moving from the deepest areas in the south (with some of the oldest plant types in the deepest soil) to the north, where the shallow depth limits choices to survival species that can thrive in four inches of soil. All three plant adaptation strategies are represented: the “competitor” that maximizes resource acquisition, the “stress tolerator” that thrives through metabolic performance in unproductive niches, and the “ruderal,” or genetic propagator, that survives through rapid completion of its lifecycle in disturbed areas. Ritchie’s intention is for the plantings to migrate and change naturally as they vie for resources, producing a “wild garden,” an ever-changing landscape of evolutionary competition at work, exploiting every part of the ecological triangle.

By placing this artwork outside and having it include living plants, Ritchie has ensured this garden will be experienced very differently from a conventional indoor artwork, changing from hour to hour, growing from season to season, and welcoming humans, birds, bees and butterflies alike.

During a visit to the FDA campus in October 2014, Ritchie introduced his artwork to an assembly of employees and visitors with these remarks:

“This leggy form described by the garden’s paved pathways is a diagram of an ivermectin protein molecule, which is a cross between the inorganic (or the chemical) and the biological. That molecule became the drawing of the garden’s ground plane, and out of it come two sets of forms, one of which is very crystalline. In the middle of the garden are four metal trellises that represent the four amino acids, forming the centerpiece, and then inside that are various plants: life itself, growing outward in all of its forms.

“Darren and I took the premise of an ecosystem as a model of time, so the deeper the roof gets, the older the plants get. These are the plants from the very beginning. You can see how different they are: they don’t have leaves, they don’t have flowers. The ginkgos are almost unique specimens; there’s nothing left on the evolutionary tree. The ferns are from even further back in time. And as the garden’s timeline moves forward, the plants acquire first needles, and then leaves, and then flowers, and then they reach the limits of the earth, and spread out into the flat sedums and cacti, the kinds of species that can only exist in the very limit cases, where life is really hard to support.

“So the garden is really a model of space and time, and I hope that it also is a model of how to think about the relationship of culture and biology, which is really the FDA’s central mission: how do we relate to the enormous index of possibilities that nature holds for us? So, in the garden are scattered about 50 kinds of medicinal plants, used by different cultures for very different reasons, and also famine foods—things that can or cannot be metabolized by different species. It’s also a butterfly pollination garden. So, the project is designed to fulfill as many possible purposes as a garden can fulfill.

“What I hope that visitors will notice over the years is that the garden will get kind of wild. It is not a conventional garden, where everything stays in place. Some species, like the pines, will never move. Others will want to migrate all over the place, and invade and colonize, so in that way too, the garden a model of nature: some things are very static and some things are constantly moving and changing.

“My hope is that this constant transformation will be intriguing to the people who work here, that as you’re watching the garden change and evolve over years, you will see something suddenly leap up somewhere else that you never noticed before.”