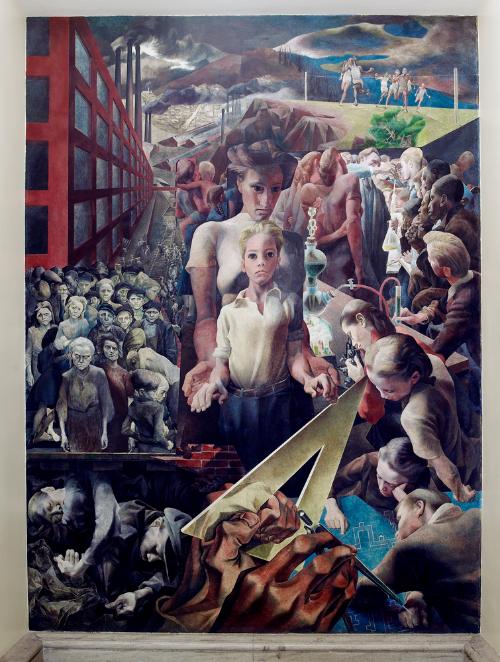

Law Versus Mob Rule

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

In Law Versus Mob Rule, a white fugitive collapses on his hands and knees before a robed justice of the law. One of the justice’s hands hovers protectively over the man’s bare shoulder while the other holds back a lawless mob set on vigilante justice. On the left side of the composition, one man restrains a bloodhound, while another holds a rope and threatens to lynch the fugitive. Originally, the face of this menacing figure was depicted as a human skull. Attorney General Homer Cummings and the Section of Painting and Sculpture objected to this and asked Curry to alter the mural. Three years later, when Curry travelled to Washington to install a different mural at the Department of the Interior building, he painted a red bandanna over the skull. While Curry depicts the victim of lynching as a white man, most lynchings in America were carried out against black men as a form of intimidation and racial terrorism. Originally, the Section asked Curry to paint a mural representing the freeing of enslaved people in the United States. This subject proved challenging and was ultimately replaced with Law Versus Mob Rule.

The painter was supposed to incorporate aspects of the Civil War, the constitutional amendment abolishing slavery, and the granting of civic and political rights to African Americans. The subject was later reconceptualized to combine the freeing of enslaved people with the welcoming of European immigrants and their impact on law and order. Realizing that the combination of the two scenes would result in a confusing composition, members of the Section of Painting and Sculpture asked Curry to redesign the panel. He presented them with a sketch titled Freeing of the Slaves, which included scenes of Civil War battles with a focus on a group of freed men and women raising their arms in joy and gratitude.

Salvatore Andretta from the Justice Department disapproved of Curry’s “halleluiah interpretation” and suggested he depict the 1857 Dred Scott decision which provoked public outrage over slavery. In agreement, Charles Moore of the Commission of Fine Arts stated, “If the subject [of emancipation] is to be handled at all in the Justice Building, a less vociferous expression of the event, and a study of its resulting benefits would seem to offer to the artist a larger field and a greater scope for his abilities.” As Moore went on to note, by 1934 the somewhat stereotypical depiction of emancipated slaves evoked by Curry had come under scrutiny by black critics. Rather than alter his representation of emancipation, Curry changed course altogether and produced Law Versus Mob Rule for the Department of Justice building. In 1942, he installed his original design, Freeing of the Slaves, in the Law Library at the University of Wisconsin.