Themes of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

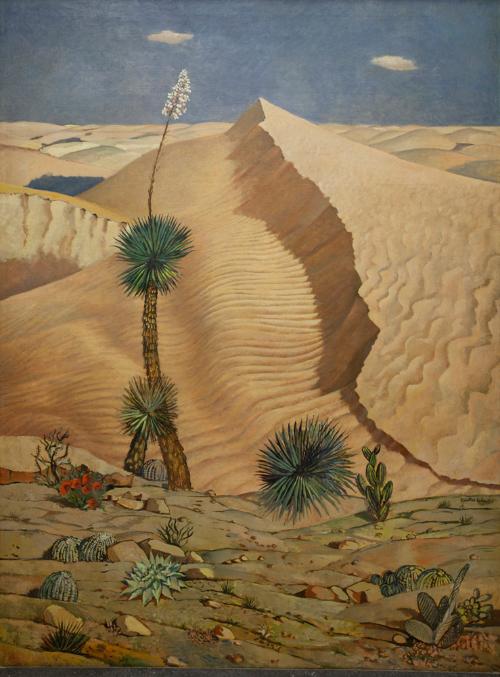

Born in Fresno, California, in 1875, Maynard Dixon had a deep appreciation of and attraction to the American West. A noted illustrator, painter, and muralist, Dixon focused his work on portraying the people and scenes of the West honestly and without embellishment. He often painted scenes of early settlers, cowboys, Native Americans, and the arid landscapes of the Southwest.

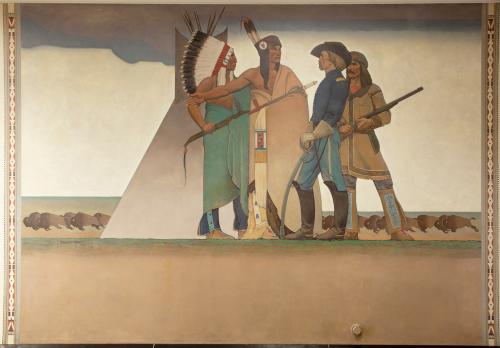

These two panels depict how life had changed for Native Americans in the nineteenth century. The stampeding buffalo in Indian and Solider shows westward migration and encroachment upon the Native Americans’ land. Dixon wrote that the chief’s gesture, with his outstretched arm, signals: “This is our land. You shall drive us no further.” The chief holds a peace pipe, but behind him another man holds a weapon at the ready.

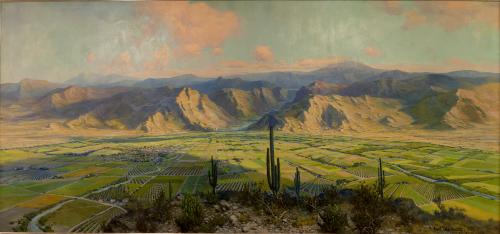

Indian and Teacher represents the generational loss of cultural identity and conflicting ideologies. Dixon wrote: “The White Man says, ‘The ground belongs to us.’ The Indian says: ‘We belong to the ground.’” To claim ownership of the land, fences are built. For Dixon, the fence included in this mural symbolizes the “divided lands and the end of freedom.” The mix of traditional and western-style clothing on the two adults contrasts with the all western-style clothing on the youth, representing the loss of cultural identity. The large ear of corn, a symbol of fertility, and which the woman holds like a baby, lends the scene a sense of tenderness. Dixon wrote: “I had always felt something far more tragic in all this, but perhaps there is now also something of hope.”