Great Codifiers of the Law

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

In March of 1935, Boardman Robinson was asked by the Section of Painting and Sculpture to paint the Great Codifiers of the Law. To determine the subject matter of this series, Robinson consulted with legal experts to identify important ancient codifiers of law as well as English common law authorities and early American lawmakers. After finalizing the arrangement of figures and scenes in the fall of 1936, Robinson worked for another year sketching, designing, and painting the murals.

Upon the completion of the murals in November of 1937, Edward Bruce, Director of the Section of Painting and Sculpture, wrote to a Washington Post reporter, “Robinson’s pictures are, I believe, without question the most distinguished piece of work which has ever been done by an American artist…. I honestly feel that it constitutes a landmark in American artistic history to have these murals installed.” In a press release, he reiterated, “without waiting for the test of time it is safe to say that Robinson’s series of great figures in the history of law will rank among the most notable achievements of modern mural paintings.” At 1,025 square feet, they constitute the largest group of panels executed by a single artist under the Section.

The series begins with three ancient theocratic lawgivers: Moses, Menes, and Hammurabi.

Moses (c. 14th-13th century BCE) - Moses was a Hebrew prophet believed to have received the Ten Commandments, which serve as the fundamentals of Hebraic law later embedded in the Old Testament. Robinson’s legal advisors argued that the Ten Commandments serve as a moral code rather than a legal one, making the inclusion of Moses complicated. However, on the advice of others, Robinson opted to include this representation of Hebraic law. In the mural, Moses alludes to the divine origins of the Ten Commandments by pointing to the heavens with his right hand and then down to the laws and people with his left.

Menes (c. 3200 BCE) – Menes is believed to be the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty of Egypt and is commonly recognized for unifying the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt and founding Egyptian law. Though no document or formal code of law has been preserved, Egyptian law was administered for centuries and influenced Greek and Roman lawmakers. Menes is depicted with pyramids behind him as a scribe at his feet transcribes his words on a papyrus scroll.

Hammurabi (c. 1810-1750 BCE) – Hammurabi was a king during the First Babylonian Dynasty. He is often identified with the Code of Hammurabi, which was a set of laws known for harsh disciplinary action for criminal behavior and for protecting a suspect’s right of innocence until proven guilty. When the mural was painted in the 1930s, the Code of Hammurabi was the earliest known example of a written legal code, thanks to the 1901 discovery of an ancient stone stelae upon which it was inscribed. Robinson depicted Hammurabi with a conical crown and long beard likely based on the carving of Hammurabi from this stone stelae.

Facing the ancient lawgivers across the hall are three Greco-Romans: Solon, Justinian, and Papinian.

Solon (639-559 BCE) – A statesman, legal reformer, and poet, Solon was elected chief magistrate of the city of Athens in 594 BCE. During his service, he enacted political and economic reforms that empowered peasants and placed limitations on the rights of the nobility. He is thus known as the founder of Athenian democracy. In the panel, Solon holds the scales of justice in perfect balance while two young men below him represent the shepherds and farmers on whose behalf he issued his reforms.

Justinian (c. 483-565) – Justinian ruled the Byzantine Empire from 527 to 565. One of his greatest achievements was the codification of Roman law through the creation of the Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of the Civil Law), which serves as the basis of modern civil law. In his right hand, Justinian holds a mask, which Robinson described as the “mask of piety” which the tyrannical emperor hid behind to aggregate power based on religious justifications. Below the emperor, a man struggles to hold the weight of Justinian’s tomes.

Papinian (c. 142-212) – Aemilius Papinianus, known as Papinian, served as praetorian prefect, or chief advisor, to Emperor Septimius Severus, who ruled the Roman Empire from 193 to 211. He authored more than sixty legal texts, many of which proved influential in composing the Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of the Civil Law) three centuries later under the rule of Justinian. Robinson depicts Papinian as a thoughtful scholar in a red robe with a dedicated student at his feet.

Between the ancient theocratic lawgivers and the Greco-Romans are depictions of the signing of the Constitution and the Magna Charta, as well as portraits of English judges Coke and Blackstone and American judges Marshall and Kent.

Constitution (1789) – The fundamental law of the United States, the Constitution was drafted in 1787 and ratified in 1789. This panel features George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, who was in poor health at the time of the signing, flanked by other signers of the Constitution, including James Madison, James Wilson, John Rutledge, Charles Pinckney, Rufus King, and Gouverneur Morris. The panel is notable for the inclusion of a young African American figure, who is possibly William Lee. William Lee was enslaved by George Washington as a young man and was possibly present at the signing of the Constitution. Lee gained his freedom only upon Washington’s death when he was approximately 50 years old. At the time of the Constitution’s ratification in 1789, 18% of America’s population was held in bondage, which included over 695,000 men, women, and children according to the 1790 census.

Magna Charta (1215) – The Magna Carta, also known as the Magna Charta, was drafted in the early 13th century by a group of British barons angered by the king’s abuse of royal power. After the barons rose up in rebellion, King John agreed to negotiate the terms of the Magna Charta and ratified it on June 19, 1215. In its restriction of the power of the monarchy, the charter played a significant role in British constitutional history. In the mural, King John is presented with the Barons’ demands on neutral ground at Runnymeade on the southern bank of the River Thames. Robinson includes a portrait of himself as a bearded farmer in the lower right of the composition.

Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) – An English jurist and member of Parliament, Sir Edward Coke served in a number of prominent positions during his forty-year political career, including Attorney General and Chief Justice. Coke is most recognized as a champion of the common law, and he argued against royal proclamations that were contrary to the British legal code. His writings influenced the lead-up to the American Revolution and the third and fourth amendments of the Bill of Rights, which restricted the quartering of soldiers in private homes and unreasonable search and seizure. Coke wears an elaborate red robe and an accordion-shaped collar called a ruff that was typically worn by wealthy European men and women from the mid-sixteenth to mid-seventeenth centuries.

Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780) – An English judge and member of Parliament, Sir William Blackstone served as professor of law at the University of Oxford, where he inaugurated courses in English common law. Previously, only Roman law had been taught at Oxford. Blackstone represents a bridge between the common law of England and the laws of the United States. He published his Commentaries on the Laws of England throughout the 1770s, which were read widely by American founders and are still cited today in Supreme Court opinions.

John Marshall (1755-1835) – One of the most significant judicial figures in American history, John Marshall served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1801 until his death in 1835. During his career, he strengthened the role of the judicial branch in the federal government. Through his rulings on cases such as Marbury v. Madison, which instituted the process of judicial review, Marshall succeeded in making the Supreme Court equal to the other two branches of government and the authority on constitutional matters. In the mural, Marshall stands in his judicial robes with the Great Seal of the United States behind him.

James Kent (1763-1847) – James Kent served as an attorney, state legislator, and Chief Justice of the New York State Supreme Court. In 1823, he became the first professor of law at Columbia University. His four-volume Commentaries on American Law (1826) were based on a series of lectures he gave, and they are considered the American counterpart to Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Kent’s writings became a crucial resource for American legal practitioners and scholars.

Across the hall are portraits of Thomas Aquinas, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Hugo Grotius, and Francisco de Vitoria.

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) - Thomas Aquinas was an Italian philosopher, theologian, and Dominican friar. Through the writing of almost eighty works, he attempted to resolve the conflict between faith and intellect. His Treatise on Law recognized four types of law—eternal, natural, human, and divine—with a special interest in the relationship between human nature and morality. Ultimately, the Treatise on Law helped form the basis for Catholic canon law. In a church-like setting, Aquinas in his priestly habit gestures to heaven with his right hand under a vaulted ceiling while holding a bible in his left.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1935) – An American attorney and law professor, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., served on both the Massachusetts State Supreme Court (1882-1902) and the United States Supreme Court (1902-1932). A widely cited and influential judge, he became well known for his liberal interpretation of the Constitution. A cornerstone of Holmes’s judicial philosophy was his belief that "the life of the law has not been logic, but experience," which is quoted in one of the murals by George Biddle in the Department of Justice building. Holmes passed away in March of 1935 just as Robinson began the mural cycle.

Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) - A Dutch jurist and humanist, Hugo Grotius is often referred to as the “father of international law.” In 1625, he wrote the three-volume De Jure Belli ac Pacis (On the Law of War and Peace), which became one of the earliest definitive texts on international law, along with those of Alberico Gentili and Francisco de Vitoria, pictured to the right of Grotius. Robinson depicted Grotius along a shoreline gesturing toward a departing ship, suggesting the global reach of his legal writings.

Francisco de Vitoria (1480-1546) – A Spanish Dominican friar and legal scholar, Vitoria was one of the founders of modern international law and was known for defending the legal rights of American Indians. Lacking any physical description of Vitoria, Robinson based this portrait on Dr. James Brown Scott, then the Secretary of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Upon viewing the mural, Scott wrote to Robinson, “Words fail me to express my appreciation of the magnificent mural of Francisco de Vitoria. . . . [F]rom the bottom of his heart the unworthy one whose likeness Vitoria bears on the walls of the Department of Justice thanks you for the most perfect portrait he has ever had.”

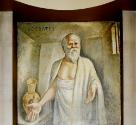

The cycle also includes two smaller panels under aluminum leaf rotundas depicting Jesus and Socrates.

Jesus (c. 4-6 BCE – c. 30-36 CE) – Jesus was a Jewish teacher and prophet who, in the Christian faith, is believed to be the Messiah and the incarnation of God. Robinson was both a political radical and a committed Christian; of the Jesus and Socrates panels, he wrote, “… I am using Jesus and Socrates for their presumed ethical significance in the development of law, or roughly speaking, civilization.” He also stated that the Jesus and Socrates panels were his most successful of the series.

Socrates (469-399 BCE) – At the basis of his teachings, the Greek philosopher Socrates advocated for a purely objective understanding of concepts such as justice and virtue. He also emphasized rational argument and knowing one’s true self. Socrates’ philosophy is recorded in the writings of his pupil, Plato, and Plato’s pupil, Aristotle. Robinson depicts Socrates in a prison cell at the end of his life, awaiting execution for impiety and corruption. Behind him, a greek vase possibly contains the poisonous hemlock he was sentenced to drink.