The Meaning of Social Security

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

In 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted a series of domestic programs, referred to as the New Deal, aimed to relieve unemployment, revive the economy, and reform the financial system. Between 1933 and 1935, President Roosevelt established four federal art programs to support American artists and make art accessible to the public. One of these programs was the Department of the Treasury’s Section of Painting and Sculpture (later renamed the Section of Fine Arts), which focused on procuring high quality artwork through anonymous competitions.

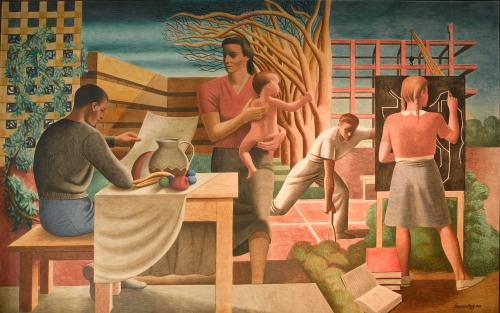

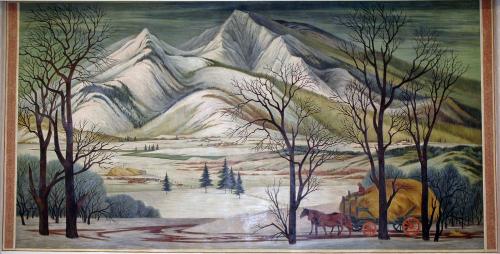

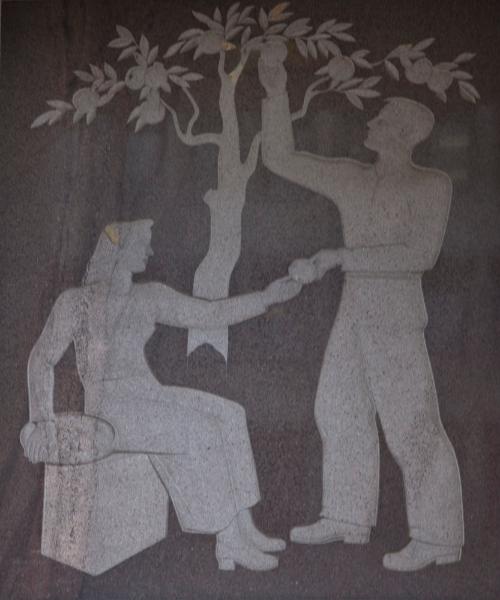

As part of the New Deal, President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act into law on August 14, 1935. Five years later, the Social Security Administration Building was designed by Charles Klauder and Louis A. Simon in the Egyptian revival style, and the Section undertook a competition for the decoration of the main corridor of the building. From 375 entries, Ben Shahn’s designs emerged as the clear winner, chosen unanimously by a jury of four accomplished American artists.

The jurors praised “the indications that the artist drew from life, not relying entirely on his or her supreme knowledge of design” and the “variety in the tempo and texture” of the design. They also admired the pattern, color, continuity, power, and imagination evident in Shahn’s sketches.

Shahn reveled in the goals and challenges of the project. Upon receiving the commission in October of 1940, he wrote to Edward Bruce, director of the Section: “To me, it is the most important job that I could want. The building itself is a symbol of perhaps the most advanced piece of legislation enacted by the New Deal, and I am proud to be given the job of interpreting it, or putting a face on it.” After many months of work, the mural cycle was unveiled on June 17, 1942.

Ben Shahn was born in Kovno, Lithuania, in 1898. At the age of eight, he and his family immigrated to the United States, settling in Brooklyn, N.Y. At fourteen, Shahn began an apprenticeship in his uncle’s lithography shop. From there, he studied at the Art Students League, New York University, the City College of New York, and the National Academy of Design.

After traveling throughout Europe and North Africa in the 1920s, Shahn returned in 1929 just as the stock market crashed and the country plunged into the Great Depression. Influenced by current events, he decided to create art that addressed contemporary social issues. Most notably, in 1931-32 he produced a series of 23 gouache and tempera paintings devoted to the trial of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian immigrants accused of robbery and murder, and sentenced (many believed unfairly) to the electric chair. Shahn painted many other socially motivated depictions of poor and working-class citizens, which earned him his reputation as a leading American Social Realist artist.

In 1929, Shahn began a friendship with photographer Walker Evans. Four years later, Shahn received a Leica camera from his brother and began to learn the craft of photography from Evans. From 1935 to 1938, Shahn worked as a graphic designer and photographer for the Resettlement Administration/Farm Security Administration (RA/FSA), documenting economic conditions in areas of the country hit hard by drought and unemployment.

As a result of his friendship with Evans and his use of the camera, Shahn grew committed to conveying the individuality of his subjects. His engagement with photography catalyzed a shift in his painting style from Social Realism to what Shahn called “personal realism.” In these paintings, he strove to depict the prejudice, bigotry, and ignorance that existed in the country while also relating the richness of spirit and engaging stories of his subjects.

In 1932, impressed by Shahn’s Sacco and Vanzetti series, Diego Rivera invited Shahn to assist on a mural at Rockefeller Center, commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller. The following year, the mural was destroyed as a result of Rivera’s unapproved addition of a portrait of Lenin. While the mural’s demolition provoked outrage in many, including Shahn, the project offered Shahn his first opportunity to contribute to a large-scale mural and his introduction to fresco painting, a valuable skill for a New Deal muralist.

Shahn, assisted by his wife Bernarda Bryson, went on to complete eight federal mural projects. His first project was for the community center of the Jersey Homesteads, a planned-living community for Jewish garment workers who came from Eastern Europe via New York City. For this project, Shahn created a fresco relating the history of the inhabitants, which paralleled his own. Shahn and Bryson then produced murals for the Bronx Central Post Office, the Woodhaven Branch Post Office in Queens, and the Jamaica, New York, Post Office, before Shahn was awarded the Social Security project.

Shahn undertook extensive research and preparatory studies for the Social Security murals. Some of the imagery came from his previous easel paintings and his photographs of the early 1930s. He also fastidiously researched the condition of the walls in preparation for painting the murals. Discovering cracks and pores in the walls’ surfaces, he requested in July 1941 that the Section replaster them; his request was refused. Around this same time, Shahn wrote to Section director Edward Bruce regarding his assistant, expert fresco plasterer John Ormai. Ormai’s draft number had been called and Shahn pleaded with Bruce to request a deferment. The request was denied, as Ormai himself was not under contract with the Section. Despite being forced to change his technique from buon or “true” fresco (painting into wet plaster) to fresco secco (painting on dry plaster), Shahn forged ahead and produced one of the most successful murals of his career.Despite their great success, Shahn’s murals have not been unanimously embraced throughout the years. During the development of his sketches, Section assistant chief Edward Rowan requested that Shahn remove an eye patch from a male figure on the west wall, stating that “every section of this long panel should be treated in a positive way.” In 1947, staff members working in the building complained that the figures on the east wall looked “pathetic” and “in poor circumstances,” and they suggested that something more cheerful be substituted. The mural garnered strong support from such art enthusiasts as Alfred Barr, Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Duncan Phillips, founder of the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., who wrote, “I am shocked to hear for the first time that Ben Shahn’s murals in the Social Security Building are in danger of being covered over or destroyed… Shahn is one of our most distinguished artists and his murals among the best executed under the Treasury project.” Nonetheless, the east wall was covered with heavy curtains into the 1970s.

The condition of Shahn’s murals has also wavered over the years. They underwent heavy cleaning and over-painting in the early 1970s. Then, in 1993, conservators discovered that the west wall had been negatively impacted by structural settling, vibration from the auditorium, and the swinging of the heavy auditorium doors. At that time, the conservators stabilized a great deal of cracking and consolidated the crumbling plaster inside the cracks. They also repaired abrasions to the east wall caused by the swinging of the heavy curtain that had covered it for years. On October 17, 1995, the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities, the Voice of America, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. General Services Administration rededicated the murals to the memory of Ben Shahn and all artists whose works enrich federal buildings.