Country Post

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

The Section of Fine Arts assigned Doris Lee a contemporary topic for her two U.S. Post Office Department murals: "The Development of the Post in the Country." In 1890, nearly 65 percent of the American population lived in rural areas. And yet, the post only went as far as the small town post office, not to individual homes or farms. In 1896, the Post Office Department began experimenting with Rural Free Delivery, a service to deliver mail directly to rural farm families, and in 1902 the service became permanent. Thirty years later, during the New Deal era, Rural Free Delivery represented democracy itself: every farmer in the nation had the same privileges of citizenship, including the delivery of mail, as every city dweller. Indeed, mail delivery to rural communities served as a vital conduit of information and a crucial link between urban and rural America. In her murals, Lee includes references to the news, commerce, transportation, and the law while she affectionately portrays familiar details of country life.

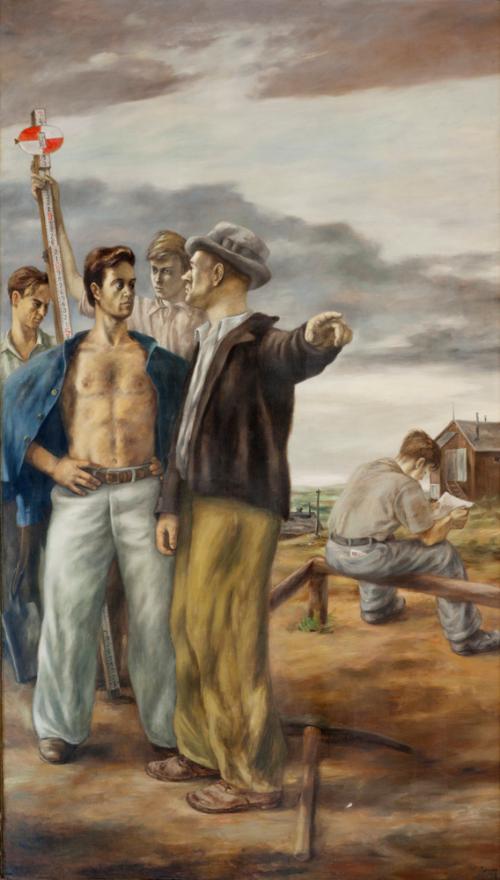

During the New Deal era, rural life was often idealized in art and the popular imagination, while in reality farmers struggled with chronically low crop prices, severe draught, and dust storms. Paintings like Grant Wood's American Gothic (1930) enshrined the farmer as a symbol of traditional American life, strong and enduring even in the face of adversities. Similarly, Lee's Country Post presents an idealized view of farm life, with a cheerful group of rural Americans enjoying the convenience of mail delivery. A farmer and his son (perhaps the same young man who reads the newspaper in General Store and Post Office) receive a shipment of tools. Behind them, the mail carrier drives an automobile. Rural mail carriers at this time supplied their own transportation, which, until around 1929, was most likely a horse and wagon. The carrier's automobile, along with the train racing toward the right edge of the painting, signify modernity, speed, and technological advancement, in contrast to the church steeple on the left, which symbolizes the endurance of faith and tradition. In the right foreground, a boy riding a horse still hitched for plowing rushes to post a letter, while a woman opens and reads hers, and even the dog and chicken appear interested in the latest news.

Additional Information

Negotiating Style: Regionalism vs. Modernism

Lee described the Post Office mural project as "a beautiful thing to be associated with." Yet, records show that Section administrators were quite critical of her work. In her initial sketches, they worried that the heads of the figures appeared too large for their bodies, and that the faces and postures were too blatantly caricatured. Even after Lee revised the sketches, the Section continued to criticize the proportions of her figures, and recommended that she hire live models, both human and animals, before submitting full-size color designs. Finally, after Section representatives made several more suggestions and Lee complied, her designs were accepted. The extent of the changes Lee made is evident in a comparison of the original sketches to the final murals.

This was not the only time Lee's work faced criticism for its exaggerated, folksy style. During the same period when she was revising her designs for the Post Office murals, her painting titled Thanksgiving was causing a sensation. Displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1935 and awarded the prestigious Logan Prize, the painting was enjoyed by many viewers for its lively depiction of women bustling in the kitchen while preparing a traditional Thanksgiving meal. However, the picture was blasted by some critics for being cartoonish, "a comic valentine to U. S. farm life." Josephine Logan, sponsor of the prize, spoke out against Lee's work, describing it as "awful." In response to Lee having won the prize, Logan founded the conservative Society for Sanity in Art, which condemned all forms of modern art.

Lee, in both circumstances, found herself caught in the crosshairs of a struggle between two artistic styles: regionalism and modernism. The regionalist movement—spearheaded by American midwestern painters Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton—aimed to depict indigenous American subjects in a realistic manner. Regionalists rejected the tenets of modernist art, which entered American culture from Europe and prized formal innovation and stylistic daring. In an effort to please the viewing public and to avoid controversy, Section administrators tended toward the conservative viewpoint, and discouraged modernist tendencies in their commissions. Lee, who began her art training in Europe painting in an abstract mode, switched to representational painting upon her return to the United States, combining aspects of both regionalism and modernism in her work.