Mail Coach Attacked by Bandits

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

The mid-nineteenth century was a time of tremendous growth for the United States. Settlers flooded west to explore the recently expanded United States territories and, beginning in 1848, gold miners rushed toward California in search of wealth and opportunity. With this mass movement of settlers came advances in transcontinental communication. Steamboats and trains moved mail across parts of the country, but reaching the west coast still posed tremendous challenges. In 1857, the U.S. Postmaster General gained the authority to contract with private stagecoach companies for delivery of the U.S. mail from St. Louis to San Francisco. Companies such as the Butterfield Overland Mail Company and the California Stage Company took up the challenge. William C. Palmer's murals address the dangers, both real and perceived, faced by mail delivery personnel and settlers during their journeys across the country.

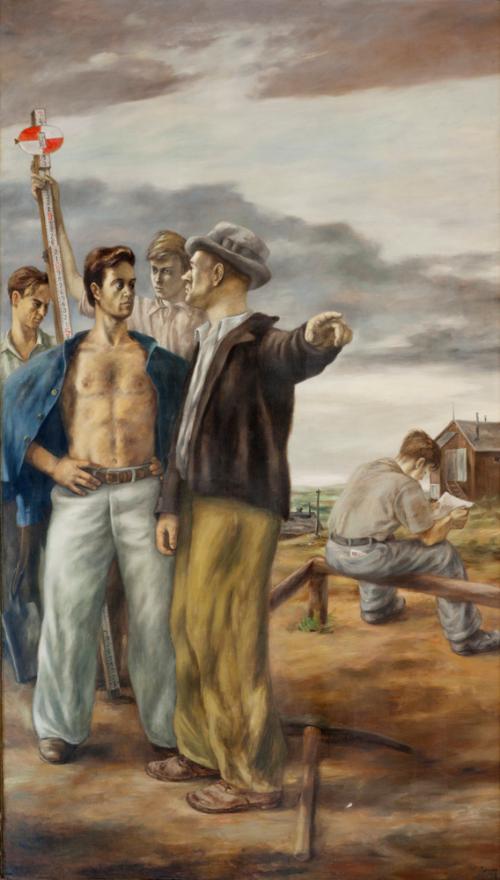

In addition to mail, stagecoach lines transported gold shipments, bank transfers, and cash in registered mail sacks. The great value of their cargo made them targets for ambushes and robberies, sometimes at gun point. Stagecoach hold-ups were not uncommon subjects for artistic depictions of the West, and some outlaws, such as Jesse James, even became legendary figures of what would later be known as the Wild West. Palmer's Mail Coach Attacked by Bandits depicts such a hold-up. A stagecoach is surrounded by three armed men on horseback. One of them reaches skyward, just struck by a bullet from the barrel protruding from the stagecoach curtain. This gun may belong to an armed guard, known as a shotgun messenger, hired to protect the cargo. One man has fallen from the stagecoach, and the driver, sitting atop a container marked "U.S. Mail," shields his face from the attack while struggling to maintain the reins of his horses.

Additional Information

The Wild West in Popular Culture

In a 1939 article on William C. Palmer's career, Esquire magazine pronounced his Post Office murals "authentic Americana: bandits and Indians attacking travelers in the Old West." Infused with a sense of nostalgia for a past that was not necessarily lived, but imagined and promulgated through art and popular culture, these pictures are true Americana, but not to be confused with historically accurate sources.

As early as the 1830s, expeditionary artists painted and sculpted scenes of the American frontier, including both glorious topographical scenes and dramatic confrontations between American Indians and white settlers. After the Civil War, as westward migration swelled, art production likewise increased, with prolific individuals like Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington producing pictures of powerful horsemen, exciting chases, and stirring battles.

In 1860, depictions of Wild West adventures began to proliferate in dime novels—popular serial stories distributed at fixed, low prices. Encounters between Indians and settlers provided one of the recurring themes of these narratives, which gained great popularity through the end of the nineteenth century. During the later decades of their run, dime novels featured bold, colored cover illustrations, often depicting dramatic confrontations among cowboys, Indians, and outlaws. In 1883, William F. Cody, or "Buffalo Bill," opened the first live Wild West show. Although many Native Americans participated in these outdoor reenactments of frontier life, including Lakota chief Sitting Bull, the performances sensationalized the "winning of the West" in ways that simplified and mythologized what was in reality a prolonged and bloody struggle. In the shows, American Indians repeatedly attacked whites and were conquered, proliferating the myth of unprovoked Indian aggression and the inevitability of European dominance.

Building on the popularity of Wild West shows, Hollywood cinema in the early twentieth century propagated the romantic myth of the Old West on an international scale. From the 1903 film "The Great Train Robbery" to the 1930s Hopalong Cassidy movies and later television shows, Hollywood maintained and even magnified the imagined scenarios of cowboys and Indians in the Wild West. It was within this cultural context, drawing on a century's worth of artistic and popular images, that William C. Palmer produced his "authentic Americana."