Consolidation of the West

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

In the nineteenth century, the rugged land of the American West held great practical and symbolic value for settlers. It offered geological grandeur, agrarian opportunity and represented, to many, the destiny of the American people. Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States was ordained to expand westward, had spiritual and religious undertones and was used to justify brutality and Indian removal. It also allowed people, even in the twentieth century, to view the conquest of the West as an inevitable progression. With scenes moving chronologically from left to right, Ward Lockwood's ambitious frescos portray one interpretation of the settlement of the American West against the backdrop of advancements in postal communication.

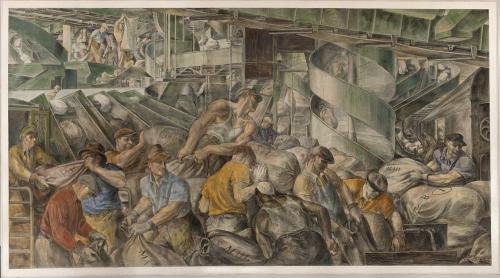

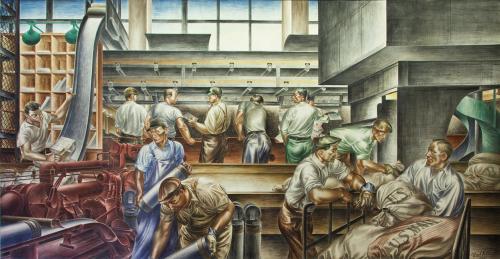

Consolidation of the West continues the story begun in Opening of the Southwest. At the mural's far left, a stagecoach descends into a deep gorge. The preferred mode of transportation before the advent of the railroad in the mid-nineteenth century, the stagecoach carried both passengers and mail. In the left foreground, men build a permanent structure, signaling the end of their journey and the beginning of a settlement. Prominent in the composition is the central mother and child. Lockwood referred to the pioneer woman as a "madonna of the plains," a symbol of love, sacrifice, and the religious foundations of the philosophy of Manifest Destiny. Behind the woman, a train represents the next advance in transportation, as the Transcontinental Railroad, which united the country in 1869, moved people, goods, and mail with unprecedented speed.

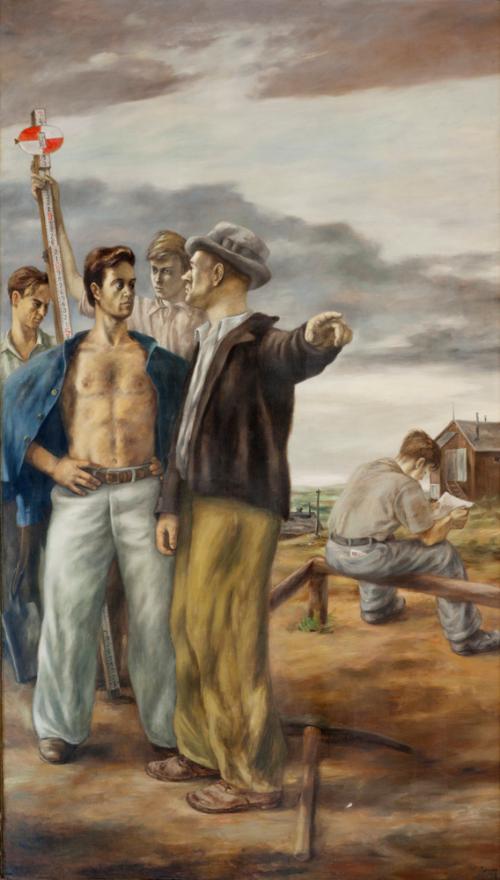

The final scene of the mural, in the right foreground, takes place in 1877, at the close of the Black Hills War, also known as the Great Sioux War. In 1868, the Treaty of Fort Laramie awarded the Black Hills and Powder River Basin (present-day South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana) to the Lakota nation. The 1874 discovery of gold in the Black Hills brought a flood of settlers, which violated the treaty. American troops were sent to defend the settlers and move Lakota and Northern Cheyenne Indians onto reservations. Tribal leaders refused, but, after defeat in several major battles, were forced to surrender. Despite the terrible loss that this war represented to the American Indian population, Lockwood depicts the surrender as peaceful, with Crazy Horse handing over his gun, likely to First Lieutenant William P. Clark.