Architecture Under Government - Old and New

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

On July 1, 1938, a twenty-two-panel mural by Harold Weston was unveiled in the lobby of the Procurement Division Building in Washington, D.C. Weston divided the artwork into three sections, which celebrate the activities of the Procurement Division of the U.S. Treasury Department. This division managed large-scale construction projects for the government and procured supplies for the federal workforce. The General Services Administration, created in 1949, took over these responsibilities and continues to oversee similar services today.

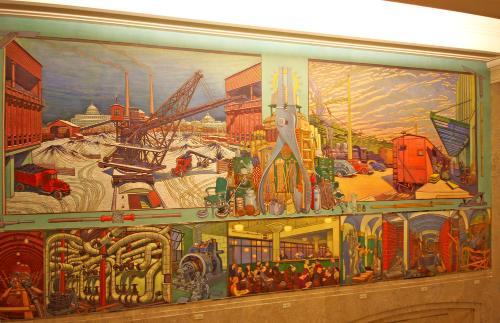

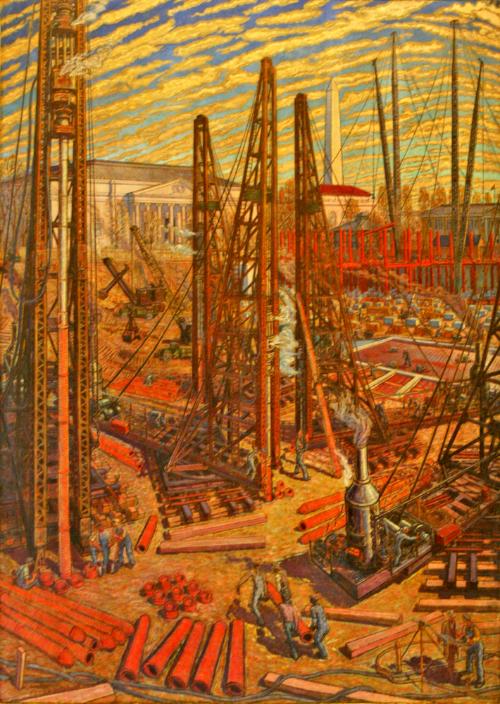

Upon entering the building, visitors encounter six large panels depicting Modern Construction above a bank of elevators. To the left, on the south wall, a large mural with seven smaller panels below portrays Architecture Under Government—Old and New. This series explores the extensive building program undertaken by the Procurement Division from 1933 to 1937 during the Great Depression. On the north wall, Supply Branch of Procurement, has a similar arrangement of panels that shows how the Division secured fuel and resources for federal buildings across the country.

In Architecture Under Government - Old and New, Weston divides the large upper panel into two scenes, showing new federal buildings on the left and old government buildings on the right. Dividing the two compositions is a collection of architectural tools, which includes a sheaf of paper, a bow compass, and a T-square. In the left scene, New Buildings Built by the Government, Weston assembles buildings from across the country in one urban landscape. He called these imagined arrangements, “galaxies” of architecture. Cars make a turn around the Federal Trade Commission building at center, which is accurately pictured next door to the National Archives in the Federal Triangle in Washington, D.C. Acute observers will be rewarded with a host of details, such as the inclusion of two monumental sculptures outside the Federal Trade Commission, which Michael Lantz had recently sculpted, titled Man Controlling Trade. However, across the street, he placed the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse, which is in New York City. These “galaxies” were challenging because they required a great deal of precision to capture the many details of well-known buildings. The artist also had to invent a new urban plan that could fit the buildings in a cohesive and sensible way. As Weston wrote in 1938, “The architectural end is honestly about the hardest thing I have ever tackled.”

On the right, Older Buildings Built by the Government similarly arranges historic buildings from across the country into one reimagined urban center. While cars zoom around in the other composition, this scene features horse-drawn carriages clattering down cobblestone streets. At center is the Treasury Department building with the Washington Monument rising behind it. To the right of the monument, Weston includes Alfred B. Mullet’s State, War, and Navy building, which is now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. While these three structures are in Washington, D.C., the large rotunda pictured on the right is the Old Post Office and Courthouse in Chicago, Illinois.

Below the large panel are seven small panels that show the interior workings of the offices of architects, engineers, accountants, stenographers, and archivists at the Procurement Division. Taken collectively, the scenes depict the enormous human effort required to plan and construct these monumental buildings. Moving from left to right, Office Scene shows a clean, orderly line of desks with workers reviewing documents or talking on telephones. A few women provide clerical support as they take dictation. The next panel, Architectural Design and Drafting Room, portrays two architects or engineers in the foreground consulting an architectural elevation drawing at a drafting table with the tools of their trade close by. In Office Equipment, a man operates a multilith machine, which in the 1930s was the latest in printing technology available. The central panel, Treasury Department and Procurement Division, displays a map of the United States illustrating the department’s construction activity across the country from 1933 to 1937. During those few years, a remarkable total of 1,895 new federal buildings were constructed or in development. To the right, Multigraphing, reveals the accounting office where new tabulating machines could do the work of fifty clerks. In the panel, a man feeds perforated cards encoded with basic calculations into a machine. The next task featured in the panels is Making Blueprints. In this room, a network of exhaust ducts removes the hot air produced by gas-heated rollers that ran twenty-four hours a day drying prints. In the final panel, Filing, archivists store away documents in the basement of the building. The federal government produced an amazing number of records during the New Deal, which are now housed at the National Archives and Records Administration.

Together the small panels highlight the busy and productive offices of the Procurement Division, where the staff appear as industrious as the latest machines. By placing these panels beneath the large mural celebrating the government’s architecture, Weston implies that many people and hours of work were required to accomplish these massive construction projects. The Procurement Division as pictured by Weston is harmonious with each employee carrying out his or her task to help the agency achieve its objectives.

From January 1936 to May 1938, Weston with the assistance of Philip Bell painted the series in his one-room studio in the Adirondack Mountains near St. Huberts, New York. The artist sometimes worked eleven-hour days. In a letter to a friend dated May 13, 1938, he wrote, “Tonight I can write that the mural is finished. After almost two and a half years that deserves a whole paragraph.” Weston had never previously worked on such a large commission, and it proved to be the only public mural completed by the artist. After the panels were shipped to Washington, D.C., he supervised their installation, even touching up a few panels on-site because of the dim lighting.

![[unknown - fountain] by Theodore J. Roszak](/internal/media/dispatcher/31171/preview)