Modern Construction

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

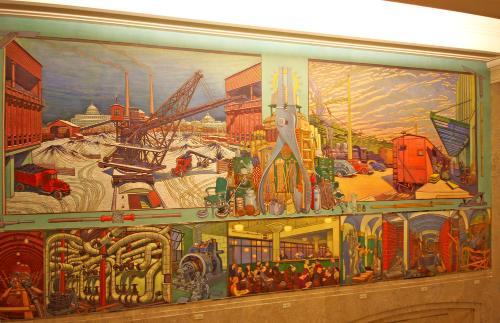

On July 1, 1938, a twenty-two-panel mural by Harold Weston was unveiled in the lobby of the Procurement Division Building in Washington, D.C. Weston divided this series into three sections, which celebrate the activities of the Procurement Division of the U.S. Treasury Department. This division managed large-scale construction projects for the government and procured supplies for the federal workforce. The General Services Administration, created in 1949, took over these responsibilities and continues to oversee similar services today.

Upon entering the building, visitors encounter six large panels depicting Modern Construction above a bank of elevators. To the left, on the south wall, a large mural above seven smaller panels portrays Architecture Under Government—Old and New. This series explores the extensive building program undertaken by the Procurement Division from 1933 to 1937 during the Great Depression. On the north wall, Supply Branch of Procurement, has a similar arrangement of panels that shows how the Division secured fuel and resources for federal buildings across the country.

In the Modern Construction series, the six panels above the elevators, Weston celebrates the work and the variety of buildings erected across the country by the Procurement Division. The series explores the physical labor and many skills required to put a building together. While a construction site can seem a messy business, Weston reveals the underlying order required to finish a building from securing the foundation to laying the roof. Workmen accommodate uneven terrains and unpredictable weather in different climates, while still managing to get the job done.

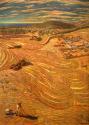

In the far-left panel, Surveying, Weston paints workmen leveling the landscape and laying the foundation of a naval hospital outside of San Francisco. A slice of the Pacific Ocean appears along the horizon line. In the foreground, two surveyors use a theodolite on a tripod to find the vertical and horizontal angles of the land. Large earth movers crisscross the terrain to prepare a level ground for the foundation, which is beginning to materialize on the right side of the canvas.

In the next panel, Pouring Concrete, Weston shows the support structure of a government building near Seattle, Washington. Against the mountainous backdrop, workmen accommodate the uneven topography by laying concrete at different levels. The artist created a busy composition, showing various methods of pouring concrete from carting wheelbarrows to using long troughs to carry concrete to a foundation bed. Weston centers the men’s labor as integral to the construction of the rising structure. A diverse workforce labors on the construction site, but that diversity vanishes in his depictions of office settings from the 1930s. Weston observed the different locations he depicted and recorded the social conventions of his day.

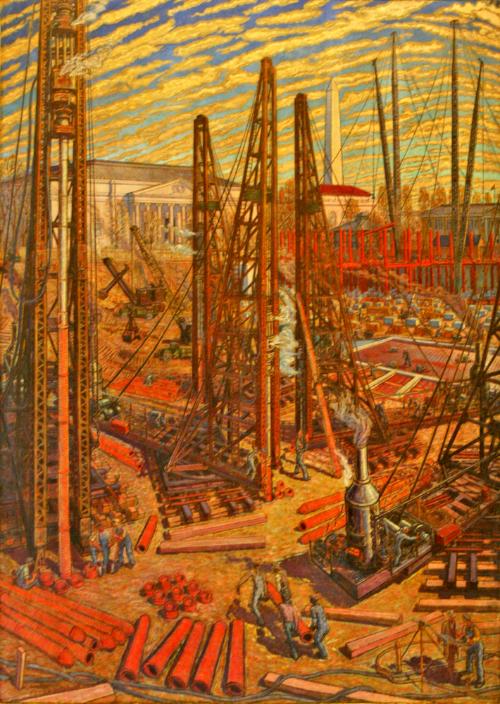

In Steel Foundations, the artist shows the construction of the U.S. Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C. Beyond the large pit sits Constitution Hall on the left, and the Washington Monument on the right. Inside the excavated area, towering pile drivers use steam power to lift and drop heavy weights that drive piles into the soil to stabilize the foundation. Weston traveled to these various sites to capture details about the construction equipment such as the smoking steam boiler in the lower right corner of the panel. The composition suggests chaos with its throng of machines and scattered mounds of construction materials. In contrast to the orderly offices of the Procurement Division pictured in the other panels, here Weston explores the disarray and sometimes confusing nature of building construction.

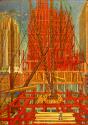

The large steel frame of a skyscraper in New York City looms in the next panel, Steel Superstructures. Dwarfed by the towering form they scale, these workmen appear uncowed by the dangerous heights and large steel beams they guide into place. Massive cranes transport beams and large wooden planks in the air. The planks are laid across the steel structure to support the crane’s weight as it ascends each floor with the rising tower. Weston shows how each steel beam is encased in concrete to fireproof the building and prevent the steel from bending in the event of a fire.

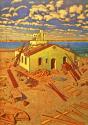

In Brick Work, Weston depicts the completion of the exterior of a post office and courthouse in a New England town. Many of these dual-purpose structures popped up around the country in the 1930s and often adopted the architectural traditions of their locale. In this case, the use of brick in this Georgian style building suited the New England backdrop. Construction materials such as stone, brick, and bags of sand are stacked in the foreground. On the left, men feed sand into a mixer to create mortar while other workers shuttle the freshly prepared mixture down planks to the job site where it will be used to finish construction.

In Roofing, the final panel, roofers hoist long timber planks and notch rafters on the roofline of a quarantine station in Miami, Florida. Quarantine stations received newly arrived immigrants and placed anyone infected with diseases in quarantine until it was deemed safe for them to enter the country. These facilities, which now are monitored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), can still be found across the country at entry and land-border crossings. In contrast to the New England post office and courthouse in the preceding panel, this building uses materials common to the region’s tropical climate such as stucco, which has the appearance of plaster but is made from cement, sand, and lime.

From January 1936 to May 1938, Weston with the assistance of Philip Bell painted the series in his one-room studio in the Adirondack Mountains near St. Huberts, New York. The artist sometimes worked eleven-hour days. In a letter to a friend dated May 13, 1938, he wrote, “Tonight I can write that the mural is finished. After almost two and a half years that deserves a whole paragraph.” Weston had never previously worked on such a large commission, and it proved to be the only public mural completed by the artist. After the panels were shipped to Washington, D.C., he supervised their installation, even touching up a few panels on-site because of the dim lighting.

![[unknown - fountain] by Theodore J. Roszak](/internal/media/dispatcher/31171/preview)