Supply Branch of Procurement

Fine Arts Collection

U.S. General Services Administration

On July 1, 1938, a twenty-two-panel mural by Harold Weston was unveiled in the lobby of the Procurement Division Building in Washington, D.C. Weston divided the artwork into three sections, which celebrate the activities of the Procurement Division of the U.S. Treasury Department. This division managed large-scale construction projects for the government and procured supplies for the federal workforce. The General Services Administration, created in 1949, took over these responsibilities and continues to oversee similar services today.

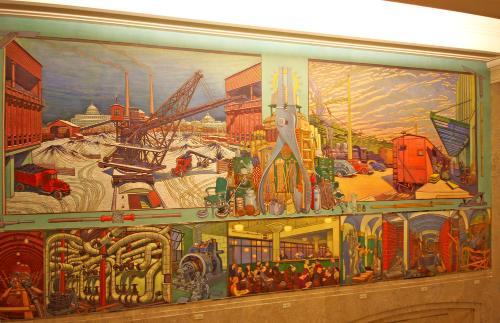

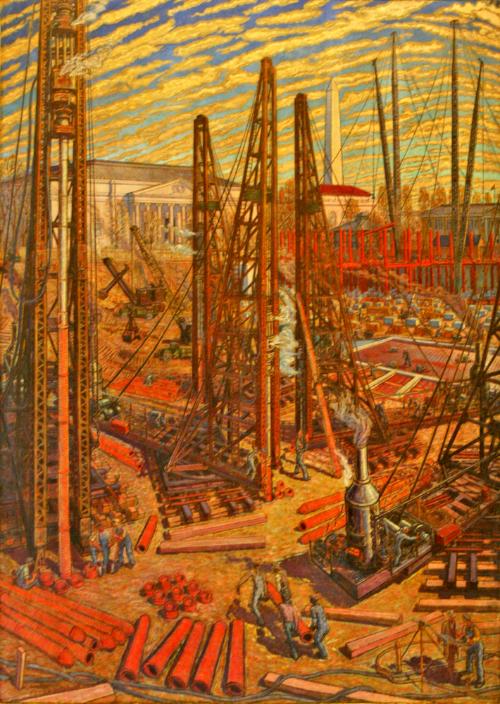

Upon entering the building, visitors encounter six large panels depicting Modern Construction above a bank of elevators. To the left, on the south wall, a large mural with seven smaller panels below portrays Architecture Under Government—Old and New. This series explores the extensive building program undertaken by the Procurement Division from 1933 to 1937 during the Great Depression. On the north wall, Supply Branch of Procurement, has a similar arrangement of panels that shows how the Division secured fuel and resources for federal buildings across the country.

In Supply Branch of Procurement, Weston explores how the government centralizes the procurement of supplies and services for federal employees and construction projects. The large upper panel shows two scenes at the Procurement Division Building, the same building where these murals are located: Fuel Depot on the left and Loading Platform on the right. In Fuel Depot, the artist paints the coal yard of the Capitol Power Plant in southeast Washington, D.C., which supplied fuel to heat federal buildings in the capital. In the distance, the domes of the Capitol and the Library of Congress appear along the horizon line. Weston stages the scene after a snowstorm, contrasting the white pristine snow against the mounds of black coal peeking through. By highlighting this dirty and seemingly unremarkable site, the artist underscores its essential function to the government. One truck on the right receives a load of coal, and repeated tire marks in the snow suggest the many trips required to heat buildings across the city on a cold winter day.

In Loading Platform, workers unload a train car at the building. When Weston painted these murals, freight cars unloaded supplies every day, and within a week, as much as $600,000 worth of materials could be delivered. Between the two scenes, the artist includes an eclectic pile of materials sourced by the Procurement Division for government agencies. An enlarged set of pliers and a ring of lights add structure to what is an otherwise bewildering variety of equipment, including office chairs, brooms, buckets, an axe, a funnel, a ladder, and even a badminton racket among other supplies.

In the smaller panels below the large mural, Weston showcases the construction and engineering services of the Procurement Division. In the far-left panel, Tunneling, the artist shows the construction of a tunnel that carries heat pipes underneath federal buildings. Four workers position a large hose to pour wet concrete that will reinforce the interior walls of the tunnel. From 1933 to 1936, the Procurement Division constructed seven miles of tunnels connecting buildings in Washington, D.C.

In the next panel, Heating, Weston reconstructs the twisting steam pipes at a heating plant in Washington, D.C. In the foreground, a workman adjusts a pump that draws condensed steam from large white boilers on the right. In the Turbine panel, the artist faithfully records one of the turbines that helps run an office elevator, showcasing his careful attention to the details of this machine and others he researched. Elevators in a modern office building of the 1930s required annual maintenance. In the panel, a workman checks the electric motor that activates the brakes on each floor. In the foreground, a mechanism called the governor stops the elevator if it accelerates beyond a pre-set speed.

Weston highlights the theater of government contract bidding in the panel, Bids for Contractors. In an open room, an assembly of White men and women, who represent different businesses, offer competitive bids for government contracts. Behind a counter, a man on the right opens the bid, which is recorded by the man standing next to him. The woman at center reads the bid aloud while a supervisor on the left oversees the proceedings to ensure fairness. Businesses were invited to compete for government contracts for an array of goods and services, and typically, the lowest bidder won the contract.

In Carving, the painter mocks another form of government procurement: fine art commissions and the artist relief programs, which hired artists like Weston. He portrays a sculptor ham-handedly applying the finishing touches to a statue of Lady Justice. Usually shown blindfolded and holding a pair of scales to demonstrate her fairness, Weston’s Lady Justice peeks around her blindfold at the viewer and gives a knowing smirk. He lampoons what he thought was the over-serious approach of some art commissions, such as the extensive sculptural program in the U.S. Department of Justice building. In a newspaper article, the artist noted “it’s all in good fun” when asked about this satirical panel.

Workmen finish an interior hallway in the next section, Brick and Plaster Work. After laying terracotta tiles on the walls, workers coat the tiles with a smooth plaster finish. In the final panel, Painting, Weston includes a portrait of himself as one of several painters hired by the government during the New Deal. The mural on the wall references a controversial painting, titled Dangers of the Mail by Frank Mechau at the William Jefferson Clinton building in Washington, D.C. The mural sparked fierce discussion during the 1930s because of its depiction of nude women and historical inaccuracies, and it has continued to stir debate in recent years because of its stereotypical depictions of American Indians and women. Weston includes a caricature of himself as an unaware painter oblivious to the level of scrutiny his mural will receive after its unveiling.

From January 1936 to May 1938, Weston with the assistance of Philip Bell painted the series in his one-room studio in the Adirondack Mountains near St. Huberts, New York. The artist sometimes worked eleven-hour days. In a letter to a friend dated May 13, 1938, he wrote, “Tonight I can write that the mural is finished. After almost two and a half years that deserves a whole paragraph.” Weston had never previously worked on such a large commission, and it proved to be the only public mural completed by the artist. After the panels were shipped to Washington, D.C., he supervised their installation, even touching up a few panels on-site because of the dim lighting.

![[unknown - fountain] by Theodore J. Roszak](/internal/media/dispatcher/31171/preview)